The promises and perils of AI ghostwriters

More than iron, more than lead, more than gold I need electricity.

I need it more than I need lamb or pork or lettuce or cucumber.

I need it for my dreams.

The above is a poem by Racter, an artificial intelligence program and author of the enigmatically titled book “The Policeman’s Beard is Half-Constructed,” arguably the first book ever written by machine. Racter was a text generation system written in a custom programming language, INRAC, for the Z80 microprocessor back in 1984. By modern standards it was primitive, “a complicated blend of haphazardness and linguistic savvy,” pseudo-randomly stringing together words and phrases using English grammatical rules to produce its prose. Computerized Mad Libs, if you will.

“The Policeman’s Beard is Half-Constructed” is now very difficult to find in print (unless you’re willing to pay a hefty premium), but if you can find it in a local library or as an electronic copy, you may wish to give it a skim for its surprisingly whimsical and absurd creations. Here’s another:

Night sky and fields of black

A flat cracked surface and a building

She reflects an image in a glass

She does not see, she does not watch.

Sure, it’s not Frost or Dickinson or Wordsworth, but it’s not bad for a nearly 40-year-old bit of code.

In 1985, the software company Mindscape released a commercial edition of Racter for IBM PC, Amiga and Apple II computers. This commercial version failed to retain some of the full character of the original poetry generator. Instead, Mindscape converted it into a kind of interactive game where users could interact with the AI and “prompt” it to generate new text through an ongoing conversation.

For anyone following the ongoing development of large language models (LLMs) like GPT-3 or the soon-to-be-release GPT-4, the historical trajectory of Racter may sound strangely familiar—a precursor, déjà vu if you will—a small piece of computing history repeating itself on an industrial scale. A system is developed for generating narratives and prose. It gains a some fame and notoriety, and is later commercialized as a chatbot.

In this case, of course, I’m talking about ChatGPT.

LLMs exhibit far more sophistication than the simple algorithms of Racter, and can now spit out far more sophisticated and provocative poetry, and with far greater variation. These systems have absolutely astonishing facility with the English language, to the point that they now write far better than many humans. They can compose not just poetry, but also original narratives, philosophical essays, article summaries, legal briefs, screenplays, code snippets, and on and on.

We’re all still figuring out what to do with this newfound creative power, and how to manage and cope with all of the ethical and social implications that come along in its wake. While I share the concerns raised by many others far more eloquent on the topics of ethics and anthropomorphism in LLMs than I, I’ll save those concerns for another day.

Here, I’m interested in what this all means for creative tools, specifically tools for writing.

The value of human-produced writing in the age of the “content singularity”

The opening of the Pandora’s box that is generative technology means we will soon be inundated with a hyper-abundance of bot-generated content. As Gordon Brander writes:

… AI is reducing the marginal cost of producing content to zero. Content has become like clay. LLMs can remix it, summarize it, elaborate on it, hallucinate it, combine it with other content, freely transform it between text, audio, image, and back again. It seems we have achieved a kind of information post-scarcity. A regime of radical overproduction. A content singularity.

It’s clear that in a world of radical overproduction, humans will place a premium on high-quality content that has been authentically written by other humans. While this may not hold true for marketing emails, book summaries, product descriptions, news articles, and other types of written content typically written primarily for informative or commercial purposes, I believe it will hold true for fiction, essays, op-eds and other similar longer forms of prose.

Why? Language exists for the conveyance of meaning between humans. It’s fundamentally about a human relationship. As Emily Bender and Alexander Koller write in their excellent paper on the topic of neural language models:

We do not talk for the joy of moving our articulators, but in order to achieve some communicative intent.

Similarly, we do not write for the joy of banging our fingers on a keyboard or for the pain of hand cramps from tightly gripping a favored pen. Instead, we write to communicate, to share ideas. There is intention behind our words.

Those of us who read the words written by other humans read them in order to try and gain a glimpse into the minds and thoughts of others. We do it to see a small sliver of the world through another’s eyes. We want to know what other people have to say about the shared human experience.

Just like Racter’s poetry, texts composed purely by machine are sometimes amusing, but also fundamentally uninteresting for this very reason: LLMs have no communicative intent. They have nothing to say. Machines (today) cannot have communicative intent because they don’t have any sort of lived experience from which to draw from nor from which to ground the meaning of their words. To have something to say means to have lived, to have struggled, to have experienced joy and pain and anguish and awe and all those other things that come from being an embodied being. The meaning behind the words we utter finds grounding in our shared, human lived experience. As Murray Shanahan writes in Talking About Large Language Models:

Humans are the natural home of talk of beliefs and the like, and the behavioural expectations that go hand-in-hand with such talk are grounded in our mutual understanding, which is itself the product of a common evolutionary heritage.

LLMs are—by contrast—just stochastic parrots.

Because LLMs don’t know anything about the meaning of the words they string together, it’s nearly impossible (in contexts where it matters) for people to find real value in text conceived purely by machine. As writers, the more we relinquish our communicative intent to machines, the more likely we are to cheapen our relationship our readers. In any circumstance where a reader has specifically sought out the words of another human being—via blog posts, essays, op-eds, articles, books, poetry and the like—finding out that a machine did most of the work feels almost like being cheated. As Alberto Romero says in Everyone is Wrong about AI Writing Tools:

The reader values being in a trustworthy relationship with the writer, not an apparently trustworthy one.

Challenges and opportunities for AI-assisted writing tools

The systems that now flood the Internet with a glut of mediocre content are ironically the very same systems that promise to elevate the abilities of human writers. In particular, the opening up of GPT-3 through easily-accessible APIs has birthed a surfeit of AI-assisted writing tools, all of which promise to revolutionize the way we write, both by improving the quality of our prose, as well as the originality of our ideas.

In a world where human authors are competing with machines for the attention of readers, can we leverage the powers of those machines to improve our own output and win that competition? In places where quality and authenticity matter, I believe the answer to this is yes. And I believe that authors who employ LLMs and other future AI technologies as part of their writing process will inevitably have an edge over those who don’t.

But we’re not there yet. Not even close.

In a rather provocative tweet, Stephan Ango says:

The test for a good AI-assisted writing tool is simple: Would this tool help the world’s best writers write even better?

By no means do I claim to be one of the world’s best writers, nor even a good one. But, I’ve now spent time with a number of these tools: Lex, Copysmith, Jasper, Sudowrite, ParagraphAI, to name just a few. Counter to the effusive praise many of these tools receive on social media, I found my experience of all of them to be rather … wanting. I don’t believe any of these tools will help the world’s best writers write better. But that’s not to say they won’t in the future. These are early, heady days—it’s clear that we’re still figuring out just how to integrate this technology into tooling to make it genuinely useful and less of a gimmick. Maybe the seed of a promise is there, and we just need to help it grow.

In the meantime, allow me to enumerate a few of the obstacles to germination, as well as some possible paths forward.

Cognitive assistance over cognitive automation

Quotes on the value of writing as a practice for honing one’s thinking abound. A few favorites, starting with Carol Loomis:

Writing itself makes you realize where there are holes in things. I’m never sure what I think until I see what I write.

Similarly, the cartoonist Richard Guindon famously wrote:

Writing is nature’s way of letting you know how sloppy your thinking is.

And, perhaps most pertinent, a few pithy words from Paul Graham:

If AI saves people from having to write, it will also save them from having the ideas that writing engenders.

The more we outsource writing to machines, the less likely we are to think thoroughly about what we are trying to say.

The current generation of AI-assisted writing tools tend to place too much emphasis on allowing the machine to write for the user (the rare exception here might be Sudowrite, which takes a more measured approach). Prompt the system for the text, hit the generate button, and marvel as the machine magically fills the page with words. These tools have over-automated the writing process, and not for the better. While many of these writing tools claim to be assisting us in the writing process, what they actually do by virtue of their design and how they expose the abilities of the LLM is automate the writing process instead.

In AI is cognitive automation, not cognitive autonomy, François Chollet differentiates between what he calls “cognitive automation” and “cognitive assistance.” He describes cognitive automation as “encoding human abstractions in a piece of software, then using that software to automate tasks normally performed by humans.” In contrast, tools of cognitive assistance use “AI to help us make sense of the world and make better decisions.” Much of the way generative technologies such as GPT-3 or DALL-E or Stable Diffusion are embedded in tools today has pushed those tools too far in the direction of cognitive automation. They wrest creative control away from users and put it back in the “hands” of the AI.

This trend won’t last. I suspect once the initial infatuation with text-to-image art generators and other automagic applications of generative technologies has worn off, we will see the needle swing in the other direction toward assistance and creative control. What might that look like for writing tools specifically?

The obvious approach will involve relying on LLMs as editors, empowering them to make small grammatical suggestions, improve word choices for readability and correctness, or prune wordy sentences. Much of this functionality already exists in today’s tools. But LLMs can offer so much more while still refraining from allowing them to speak for us. Maggie Appleton describes one promising approach in her essay Reverse Outlining with Language Models: leverage the power of LLMs to automatically summarize paragraphs or large blocks of text to aid in reverse outlining, the process of revision that involves composing an outline of the text after writing it.

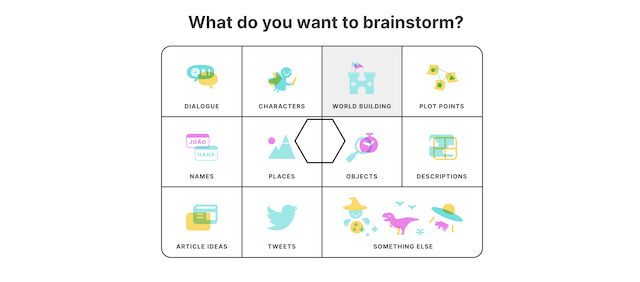

Similarly, Sudowrite takes a more measured approach to integrating AI than many of its competitors, including brainstorm functionality that allows you to use GPT as a partner in thinking through what you want to write, rather than simply giving it full license to write on your behalf. Few things intimidate writers more than the blank stare of an empty page. Enrolling AI as a partner in the ideation and brainstorming process promises to boost creative confidence, help us overcome writer’s block, and help more people get writing faster.

This way of thinking about AI-assisted writing tools not as machine-powered ghostwriters, but instead as powerful tools for thought, is exactly the right approach.

Custom models and filters for your unique voice

LLMs are, at best, just above average writers. They shine when writing about well-known topics in shorter formats where it’s sufficient to settle for average-quality writing that is cohesive, well-structured and grammatically correct. This is perfectly acceptable for many use cases, but won’t cut it if we’re talking about “making the best writers even better.”

Play with these tools long enough and you’ll quickly find that the text they generate when prompted for anything in the realm of non-fiction, reads like statistical average of all any SEO-optimized explainer article on the web. Unsurprisingly, it reflects its training data. It often lacks voice, feeling, personality, and—often—originality. It doesn’t (yet) feel like your own words. Instead, in the words of Maggie Appleton, it ends up reading more like a “B+ college essay.”

This will inevitably improve.

First, all LLMs will simply get better over time, and likely at an exponential rate (assuming we don’t run out of training material). But, more importantly, AI-assisted writing tools will eventually allow writers to train custom models on a corpus of their own writing, allowing the system to generate text in the writer’s own voice. For good writers, this could unlock a substantial productivity boon.

I already argued previously that allowing an AI to perform any writing for you is generally a bad idea. That said, the better an LLM can write in your own voice, the better it can also help edit while retaining your style and voice as well. In his essay, Photoshop for Text , Stephan Argo imagines a future where AI-assisted writing tools provide brushes and filters for text akin to the image editing capabilities of Photoshop:

Text filters will allow you to paraphrase text, so that you can switch easily between styles of prose: literary, technical, journalistic, legal, and more. You will be able to easily change an entire story chapter from first person to third person narration, or transform narrative descriptions into dialogue.

Imagine filters that perform these alterations, while still ensuring that the text conforms to how you would actually write it! That’s an incredibly powerful capability that keeps creative control and communicative intent squarely on the side of the human doing the writing.

Improved precision in prompting

Let’s talk about prompting. Though I remain critical of allowing machines to write on our behalf in all but the most banal use cases, even using LLMs for brainstorming and ideation still requires being able to tell the system what you want. The challenge is, prompting is not as straightforward as it seems. Manipulating LLMs to get what you want out of them is something of a dark art, and for those who aren’t well-practiced in how to do it, it can often feel incredibly imprecise.

Text-based prompting often works best where divergent, fanciful results are welcome, namely for brainstorming ideas for fictional creations. But, for other use cases where you might be honing in on ideas on a particular topic, it feels like playing a slot machine and hoping for three cherries every time. Oftentimes, you will type in a few sentences describing what you want, and in return receive something that vaguely resembles what you were hoping to get, followed by a stream of words that read like a non-sequitur, or possibly run counter to your original argument. It’s a frustrating user experience and not something we would typically tolerate in contexts outside of generative technologies.

These results aren’t surprising though. As I said earlier, LLMs are stochastic parrots that have no ability to understand communicative intent. And as such, they have absolutely no means to retrieve meaning from the words we give them. It’s not like working with a human ghostwriter or research assistant; machines don’t actually understand what we are asking for when we write our prompts.

Some creators of AI-assisted writing tools claim that, as this technology matures, the primary mode of production for writing will evolve into something more akin to editing and curation. These tools will save us from the supposed drudgery of thinking through the low-level production of the words themselves. But without significant improvements in how we pull what we want out of LLMs, I remain dubious of these predictions. The “raw material” of the words given to us by these systems will have to improve significantly, both in quality and in precision.

I suspect new approaches to prompt engineering and UIs that allow finer-tuned control over prompts will alleviate some of this problem. Some AI-assisted writing tools have already begun adding sliders for fine-tuning tone or style. ParagraphAI, for instance, allows you to decide whether you want the text to be more or less formal, and more or less friendly, by dragging a slider between either extreme. These are primitive beginnings; there’s still much to figure out in realm of UX for generative technologies.

Creatives in audio and visual fields—animators, graphic artists, photographers, video editors, musicians—have relied on sophisticated computing tools to aid them in their crafts for years. Computers have long been able to work adeptly with pixels, vectors, and sound waves, information easily represented mathematically. And while they have long been able to manipulate text as well, they have historically not been so adept at working with human language. Prior to the release of LLMs, the most advanced technology we’ve had for writing amounts to not much more than real-time collaborative word processors. When it comes to assisting in creative expression, the difference between Google Docs and a typewriter is minuscule compared to the difference between Photoshop and analog photo retouching.

Fortunately, this gap is narrowing. But these improvements come hand in hand with the advent of generative technologies which, if deployed poorly, threaten to surreptitiously wrest more creative control away from writers than maybe we’d like to give. It’s going to be interesting. Plenty of mistakes will be made. Nevertheless, the optimistic side of me wants to believe that if toolmakers err on the side of assistance over automation, then we might actually see a new generation of AI-assisted writing tools that truly will help the world’s best writers write even better.